In the past couple months, I’ve written a few Twitter threads (1, 2, 3) on how the contemporary Tour de France–team-centric, professional, and focused on small differences in time and speed–has diverged from the Tour of the yore, a race that privileged the individual, emphasized endurance, and contained within it the sometimes odd-to-modern-eyes core of amateurs and professionals.

These larger differences shape and are shaped by the machines, stage structures, cyclist accommodations, salaries, and negotiations between administrators and towns, to only name a few of the factors that went into the shaping of this race.

Today, I’d instead like to look at pictures. Specifically, the portraits taken of cyclists before they began the Tour.

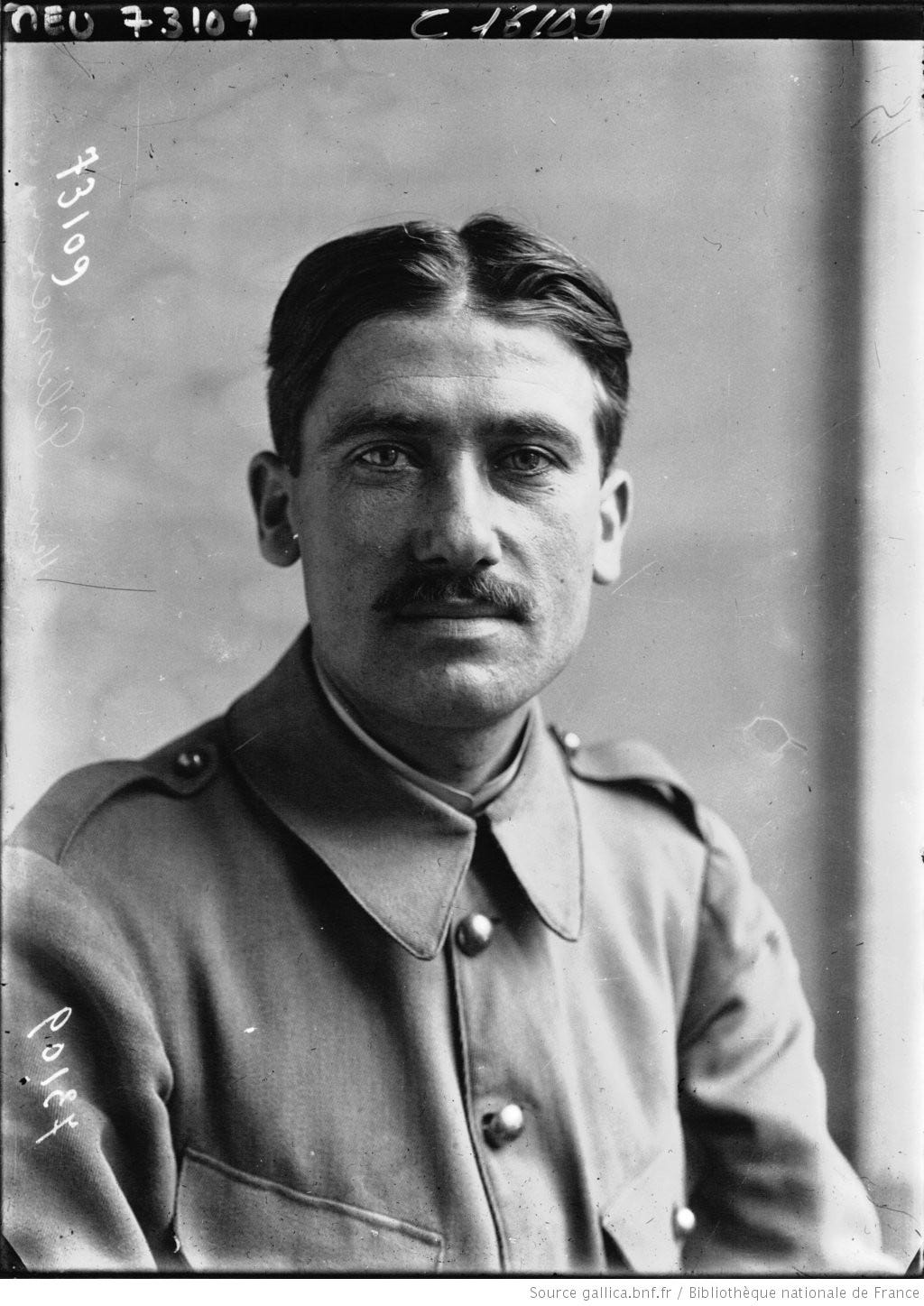

If l’Auto had printed it in color, Francis would have stood out against the forested backdrop in his horizon blues. Did he ride into town that morning, offered a single day’s leave by his commanding officer? He was then a poilu in the 19e Escadron du train, transferred in January, garrisoned not so far away. Of course the unit’s role in the war wasn’t over, so his registration might've necessitated a longer journey. Supplying other units would continue for years as the occupation went on, as soldiers and those who returned or never left rebuilt what they could. Those roads and villages and barracks and fortifications would take hard labor and materials that couldn’t be gathered from the wreckage, materials Francis’s unit helped transport.

His brother, Henri, wore the same.

Though they were separated for much of the war, they now belonged to the same unit. Best to have them apart as the fighting went on; you never knew when an entire unit could be wiped out. Now that was over, the government could make things a bit more convenient for those who would have to remain in uniform for another month, year, perhaps longer. Any time was too long for the brothers who had races to attend to, lives to continue.

The photographs were taken with a large format camera. You can tell thanks to the tonal range, the depth of the portraits–Henri’s, in particular–which comes close to lifelike. I don’t know if l’Auto had a dedicated office camera, or whether they took the portraits with the same one used on the race route: an early 4x5 Speed Graphic or the like.

They’re distinct. Henri’s appears to be taken with a longer focal length lens, his pose is direct and confident, the photograph’s contrast brings his features into sharp relief. It suits him, which is perhaps what the photographer had in mind. Henri was brash, confrontational. Francis was guarded, a bit more strategic. With a muted tonal range, he appears ephemeral, as if disappearing into the backdrop. There’s no mistaking Henri is the subject of the portrait.

Reduce the saturation, cut away the graphics, paste on street clothes and there’s still no mistaking this year’s cyclists from those in 1919. I don’t mean to make the tired argument about how romantic things were, though I’m willing to accept that might be the takeaway.

The cyclists are part of a team now, with designated roles. A Tour cyclist isn’t just a Tour cyclist, but instead a member of a larger unit. It’s how they race; it only makes sense that’s how they’re described.

The photographs are clear. One sees the jerseys down to the sponsors. What’s their identity? A cyclist. A professional one. Henri and Francis were soldiers, at least for a time. Eugène and Firmin were mechanics. The racing season began and they put on the grey and blue of La Sportive, at least in 1919, but would in time return to those other identities. Viewers knew they held onto them as they passed through their towns.

The cyclists’ pose is uniform, even if they have specialties: rouleur, climber, sprinter, puncher. Below the cyclists, not shown here, is an even longer list of those who support them, equal members of a team that desires the pinnacle of athleticism.

There are continuities, too. The contemporary cyclists’ pose recognizes a role Henri Pélissier found for himself in those early years fo the race, when others were more deferential to the “Father of the Tour,” Henri Desgrange. Pélissier claimed to “run on dynamite”: cocaine, chloroform, strychnine, etc. Him and Francis were some of the few who didn’t turn to booze, at least not regularly, at the end of a long stage. I’m not saying anything about the Groupama cyclists; I’m just saying there’s are recent Tour controversies you’re already aware of.

It’s disappointing there are few photographs of the 1919 race itself: a couple from the end of the last stage, as the cyclists rode into Parc des Princes, one or two as they left cities along the way, these portraits. Others were either lost when l’Auto’s archives went missing at the start of World War II or no one wanted to show the cyclists racing through the Western Front’s destruction.

I’m grateful these few photos at least exist.

Necessary Hawking:

You can pre-order Sprinting wherever you purchase your books.

If you’re worried about getting your copy before this year’s Tour begins, you can enter this Goodreads giveaway for a chance at winning a digital copy of the book, ending May 31st.

Once this year’s Tour begins, I’ll be chatting with Phil Klay for the book’s launch at Powerhouse Arena on July 1st. It’s virtual, so you can tune in from wherever.

I just finished reading "Sprinting Through No Man's Land" and am so appreciative of your extensive research and bringing this 100 year old story into today!

(You said it and you made it happen!)

I was able to ride with the cyclists and see and feel what they were experiencing. Their lives, the landscape around them, the terrible aftermath of the Great War, the TdF of 1919 and the true winner of the race.

It was ALL there.

Thank you Adin!

Bravo! 🚴♂️

I did 2 a day Spin classes this week, I feel like my season is in full swing! 🤣

BTW, I won't be doing two a days any time soon. Haha

Thanks Adin, loving where I'm at in "Sprinting". The last sentence describes once again so perfectly how tough these guys were, "They knew they'd have to contend with long distances on the remaining stages, on roads that had been damaged beyond what any man or country could repair in so short a time." 🚴♂️