Sources Cited: Emily Brooks

A police department's internal magazine and the criminalization of young women

Between my first book and my second, I moved from a broadly-held and shaped myth to a more closely-cultivated one. First, it was a publicity and marketing campaign that sold an international sporting event to a war-devastated population. More recently, it’s been stories around campfires that detail a campaign of state-sponsored killing largely affecting Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

How and why these latter myths form and propagate is a hydra, and one who hopes to name its heads isn’t helped by poor record-keeping. Perhaps individual Texas Rangers, one of the manuscript’s subjects, are more historically-minded than I’d like to give them credit for. They were at least interested in sharing their stories with anyone who would listen. They told each other how prisoners had attempted to escape. When the prisoner had started to run—and of course they ran, they would say—all they could do was shoot them in the back. Those who listened knew of la ley de fuga; some had taken part in similar extrajudicial killings. The justification was scarcely needed anyway: plenty thought the Texas court system couldn’t or wouldn’t handle such cases. They were only too happy to have the ranger carry out the task himself, without the impediments of a judge and jury.

Still, the accounts and justifications multiplied, an incantation that with each repetition carved a deeper groove into the historical record. Maybe other rangers just hoped to fast-track “memory’s telephone game.”

Away from large populations, with a largely sympathetic press and political system, these stories frictionlessly defined accounts of the period (though other, more recent and multi-sourced works like Américo Paredes’s With His Pistol in His Hand and Monica Muñoz Martinez’s The Injustice Never Leaves You well describe how the oppressed and oppressor are both capable of sharing their more and less true accounts, in different mediums). In a metropolis, though, the act of closely-held myths appears, at first glance, quixotic. Even if politicians and reporters are content with taking state agents at their word, many others are exposed to the officers’ acts on a day-to-day basis. A legislative and publicity game must play out for the benefit of those who’d rather look elsewhere, but there would seem to be more of a disjuncture between the stories one tells oneself and what others know to be true.

This question was only one reason I was excited to speak to Dr. Emily Brooks, author of a social history of the New York Police Department during the World War II era. Her upcoming book, Gotham’s War with a War: Policing and the Birth of Law-and-Order Liberalism in World War II-Era New York City (available for pre-order; out October 31st from UNC Press), looks at the NYPD’s conception of itself at this time, as well as how those who interacted with it viewed the department. She discusses today a more surprising form of myth-making than the ostensibly true or exaggerated “war story” swapped around a campfire: the openly fictitious short story.

Emily Brooks is a historian whose work focuses on 20th century urban history, histories of policing, women’s and gender history, and African American history. Presently, she is a Curriculum Writer at the New York Public Library’s Center for Educators and Schools. She received her PhD from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York in 2019 and taught for nine years in the City University of New York System. Gotham’s War within a War is her first book. Dr. Brooks’s work has been published in the Journal of Urban History, the Journal of Policy History, the Washington Post, the Gotham Blog, and The Metropole, among other places.

Could you trace the path of how you came upon this material?

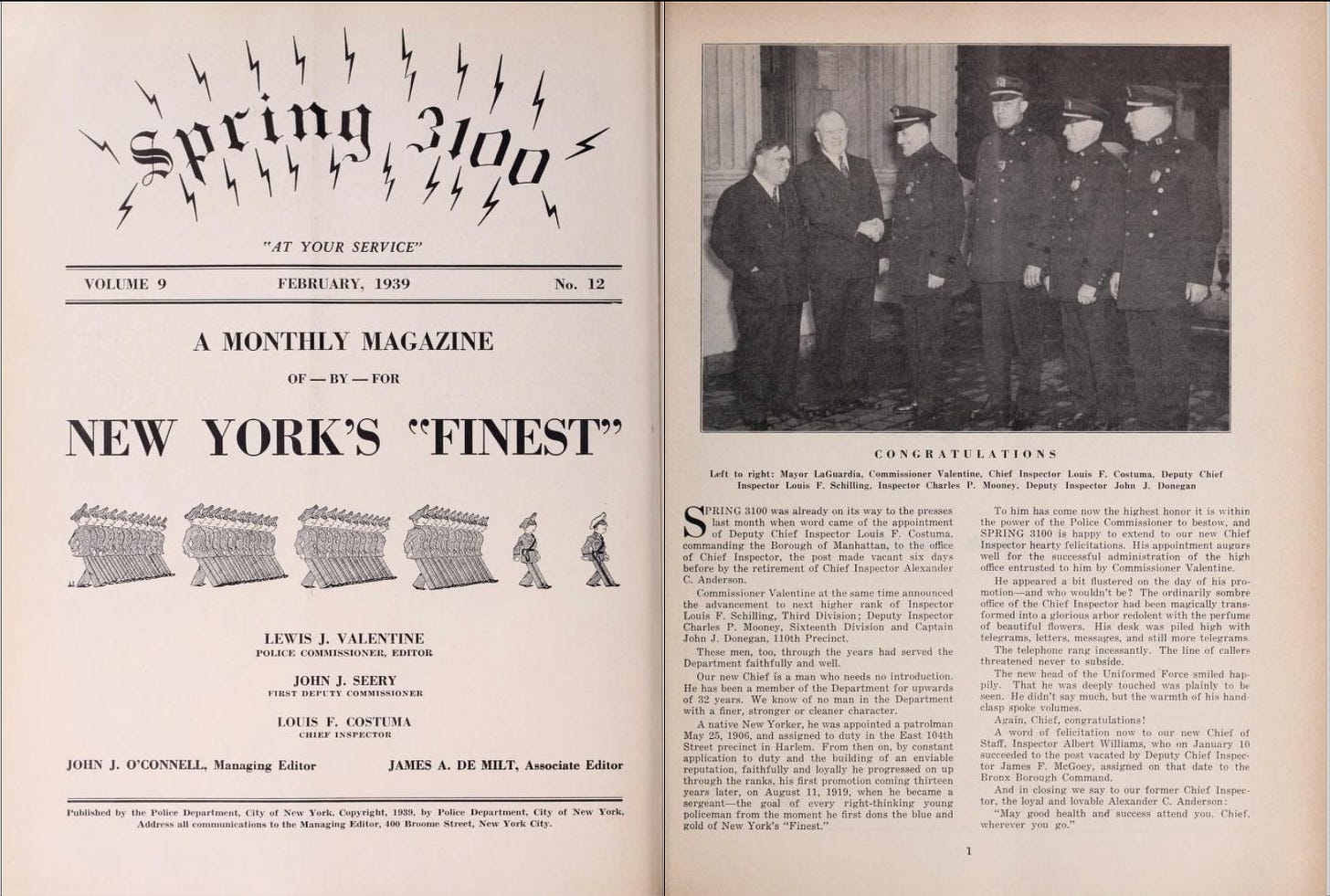

I believe I first came upon Spring 3100, the NYPD’s internal magazine (published monthly starting in 1930), after seeing them referenced in the NYPD’s Annual Reports, relatively early on in the process of researching my book. Each magazine issue was an eclectic mixture of materials produced by NYPD leadership, like speeches and updates to departmental policies, and contributions from lower level members of the department, like letters to the editor or even short stories or comics. The issues were held in bound annual collections in the stacks at John Jay College Library. I spent many, many hours reading and photographing them there.

As some context: one of the challenges in writing about the NYPD or many other police departments is that they don’t keep accessible institutional archives. This secretiveness bolsters efforts to shield departments from democratic accountability, and has extended to illegally hiding or misclassifying materials, as a lawsuit brought by the historian Johanna Fernandez has shown. The NYPD Annual Reports are useful records of how the department sought to summarize their work for the public, but they provide limited insights into how patrolmen and women view their work, internal conflicts within the department, or informal police practices.

For my own work, though, I hoped to write a social history of policing (it later became a political one as well!) which meant I was interested in the ways regular New Yorkers experienced policing as well as how both NYPD leaders and lower ranking department members conceived of their work. This type of research project involves piecing together disparate archival scraps trying to get at a larger picture from different angles (rather than focusing on the experiences of one well-known person who has one primary archival collection).

So, finding this collection of more informal monthly departmental materials in the Spring 3100 issues felt like an institutional treasure trove that vastly expanded my ability to see into the practices and the culture of the NYPD. And I would add that my approach to these materials and all materials produced in the service of state violence is to read them critically and against the grain. I read these sources, therefore, for evidence of what the police were doing and how they constructed criminality. I do not see these sources as evidence of criminality or any record of the behaviors of people who were being policed. For those perspectives, which are essential for any history of policing, I turned to many other archival collections.

How did you first interact with it?

I was captivated reading issues of Spring 3100. The magazines were an incredibly rich source because they were wide-ranging, creative, and gossipy. They summarized significant speeches given by La Guardia and Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine and included memoranda which detailed departmental policies, but they also included other surprising and in some instances more revealing contributions.

For instance, the magazines ran comics drawn by its readership. Other contributions described informal department events, like the annual summer visit to the “Police Recreation Center” in the Catskills. One year the published photos of the latter event included images of NYPD officers mocking protestors. The officers wore drawn-on facial hair and carried signs demanding “free lunch with our beer” in a playacting event titled “the Revolutionists parade.” Additionally, they ran a fictional short story every month, written by a member (or former member) of the department that was selected by the magazine’s editor, the Police Commissioner, as the “prize story” for the month. Many of them featured police officers acting heroically, or being underestimated by the public only to rise to an occasion and impress bystanders with their intelligence and physical prowess. One of these stories, which is the source I chose to highlight for this interview, proved a revealing window into the informal culture of the department.

What did the material unlock for you in your work?

The 1939 story I highlighted here followed a young white woman, who had “blue eyes” and was the “well dressed [sic] daughter of a “Connecticut merchant.” She had come to the New York City World’s Fair under duress with an older man, but was saved by a woman police officer and returned to her home in Connecticut. I selected this story because it engages with two interconnected trends in policing that occurred in the 1930s and 1940s: firstly, the increased criminalization of youth, particularly girls, and unmarried young women as part of the developing concept of juvenile delinquency and the mobilization for World War II, and secondly, the expansion of the role of women in the NYPD as a group particularly qualified to surveil these girls and children.

In the 1930s and particularly during World War II, NYPD and New York City administrators were concerned that unmarried girls and young women were traveling into the city to engage in social and sexual experimentation that might put enlisted men at risk of contracting venereal diseases. Law enforcement leaders and politicians justified the increased surveillance that NYPD engaged in as protecting young women from moral and sexual peril, which is represented in the story by the fact that the young girl is brought to the city against her will by an older predator and is happy to be sent home.

In reality, the young women who were arrested by the NYPD often did not feel that they were being saved and weren’t happy to return home or to a reformatory, detention center, or prison. Additionally many of the women picked up by the NYPD were not white daughters of wealthy businessmen in Connecticut, but rather were girls like Betty, a white teenager whose mother worked the nightshift at the Bendix aircraft plant, or Ethelene, a young Black girl who was arrested after defending herself against police brutality. Though they were heavily policed and disproportionately represented in court, Black girls rarely appeared in the pages of Spring 3100. Rather, the female juvenile delinquent was racialized as white. This depiction reflected the way that race-based notions of protection and femininity justified the policing of young women, even though in practice Black girls who were framed as outside these categories were regular police targets.

The growing role of women in the NYPD can be seen in the fact that the story features a female police officer and is written by a woman Police Academy instructor. Women had a tentative foothold in the NYPD since the Progressive Era, but they gained ground during the war as the criminalization of girls and women increased. These positions were heavily gendered and racialized, however, and the department included only a handful of Black women during these years. The growth of women in the NYPD, as well as their gendered and racialized roles, was reflected in Spring 3100’s addition of a column entitled “Strictly for the Girls” in 1944. This column was intended to appeal to women department members and wives and included recipes, advice on makeup, and descriptions of NYPD vacations. In looking through Spring 3100, I felt that I was getting a clearer sense of the culture of the police department and how its members viewed their work than in many other more official sources.

Where did it lead to next?

There were countless leads that I found throughout Spring 3100 and followed up on, but one that was particularly interesting to me was something I found in the letters to the editor of the magazine.

One of the questions my book sought out to answer was how policing changed in New York City during World War II and what impact the war had on municipal police departments. I was interested in thinking about institutional connections between the military and domestic municipal police departments. One theme that I saw running throughout Spring 3100 during the war was the way that NYPD members were encouraged to see their work policing civilians in New York as part of the war effort. The letters to the editor proved revealing windows into how effective that framing was. The department sent Spring 3100 to NYPD officers who were serving in the military (municipal police officers were not exempted from the draft so roughly 3,000 NYPD officers served in the military) and many of them wrote letters back. The authors of these letters noted that Spring 3100 “brings back many pleasant memories of our men in blue who are performing their duty at home just as we in khaki are doing abroad.”

After reading these letters, I found training materials that suggested that military police particularly prioritized experience in law enforcement in their members (this also proved true in later military mobilizations as historian Andrew Baer has shown for Jon Burge in Beyond the Usual Beating) and then that after the war La Guardia and his successor, William O’Dwyer, loosened NYPD requirements in order to encourage veterans to join the NYPD.

Are there any other materials you’d like to mention?

There were so many! One document that I really loved from this project was a memorandum to the mayor’s office related to the escape of five white teenage girls from a reformatory in Brooklyn. This extremely detailed document described how the five girls used a nail file to scrape down a lock on a window in their room, tied their sheets together, and climbed down to the roof of the building next door, eventually escaping in a taxi into the hot August night in their shelter uniforms.

This source was amazing to me because it revealed the lengths to which girls and young women went to preserve their autonomy. Additionally, after the escape the mother of one of the girls contacted the mayor and the shelter to express her anger and concern over what she saw as their negligence in letting the girls escape. In response to this parental concern, the shelter staff commented of her daughter that “nothing more could happen to her beyond what has already happened” since the girl had run away before. This callous response illustrates a number of common dynamics that girls experienced in the carceral system during these years, particularly that once a girl had engaged in sexual activity (whether consensual or not) she was less worthy of protection and in fact possessed knowledge that could endanger other inexperienced girls. It also undermined the narrative of protection that justified much NYPD surveillance of girls and young women.

Is there a librarian, archivist, colleague, or research assistant who helped you put together the pieces from these materials?

The archivists at John Jay College Manuscripts and Archives, New York City’s Municipal Archives, and New York Public Library collections, among many other institutions, were all essential for the research for my book. I was researching this book for ten years. In that time, I had the experience multiple times of new collections that were extremely relevant to my work being processed and becoming available, particularly the Health Commissioners Records at the New York City Municipal Archive and the papers of novelist and journalist Ann Petry at NYPL’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. I think researchers tend to be very conscious of the labor that goes into processing and maintaining archives, but the experience of having new collections opened while I was working on this book made me so grateful for that labor.

Also, my writing group of other women historians was really essential for keeping my research going and helping me think about how to process and analyze all of these disparate sources into one narrative project. Finding or creating a supportive community is so important when you are working on a big project alone!

Sources Cited is on hiatus during the fall semester. We’ll be back shortly with more interviews and essays. In the meantime, you can subscribe to receive the newsletter in your inbox as soon as the next issue is released. Sources Cited will remain free for all readers, but if you like what we’re doing, we appreciate you subscribing.