Welcome to the first edition of Sources Cited. For those of you just joining us, last week I described the series in a bit more detail. In each edition, released biweekly on Sundays, I’ll speak with a writer about the work that goes into their work, the stories behind their stories.

I’ll talk with each writer about a particular source (a letter, interview, photograph, map, etc.) used in their writing: how they came upon it, what it stirred in them—perhaps emotionally or otherwise intellectually—, and where it led. Some weeks it’ll look like historiography, journalism, or poetics. Whatever the discipline of the writer might be. Other weeks it will, in the parlance of Arlette Farge, be more akin to “a tear in the fabric of time, an unplanned glimpse,” an experience with a punctum in archives’ vast stores.

I’m pleased to kick things off with Kerri K. Greenidge. Dr. Greenidge is the Mellon Assistant Professor in the Department of Studies in Race Colonialism and Diaspora at Tufts University. We’re speaking to her as the author of The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family, published by in November of 2022 by Liveright. The book examines the famed abolitionist family through the side of the family less often recorded: the Black half of the Grimkes, and in particular the women of this family, prominent writers and reformers themselves. Among other accolades, The Grimkes was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography.

In selecting people for this series, one thing that stood out to me in reading The Grimkes was the way family dynamics interplay with the intellectual lives of the Grimkes. The particular manner in which this resolved itself, in the public and the private, in the Black and white halves of the family, only became clearer in talking to Kerri. I loved hearing from her about how this dialectical approach to the biography came about, starting with her work on Black press materials in graduate school. The Grimkes, to me, seems like a consummation of much of the work that she’s done to this point.

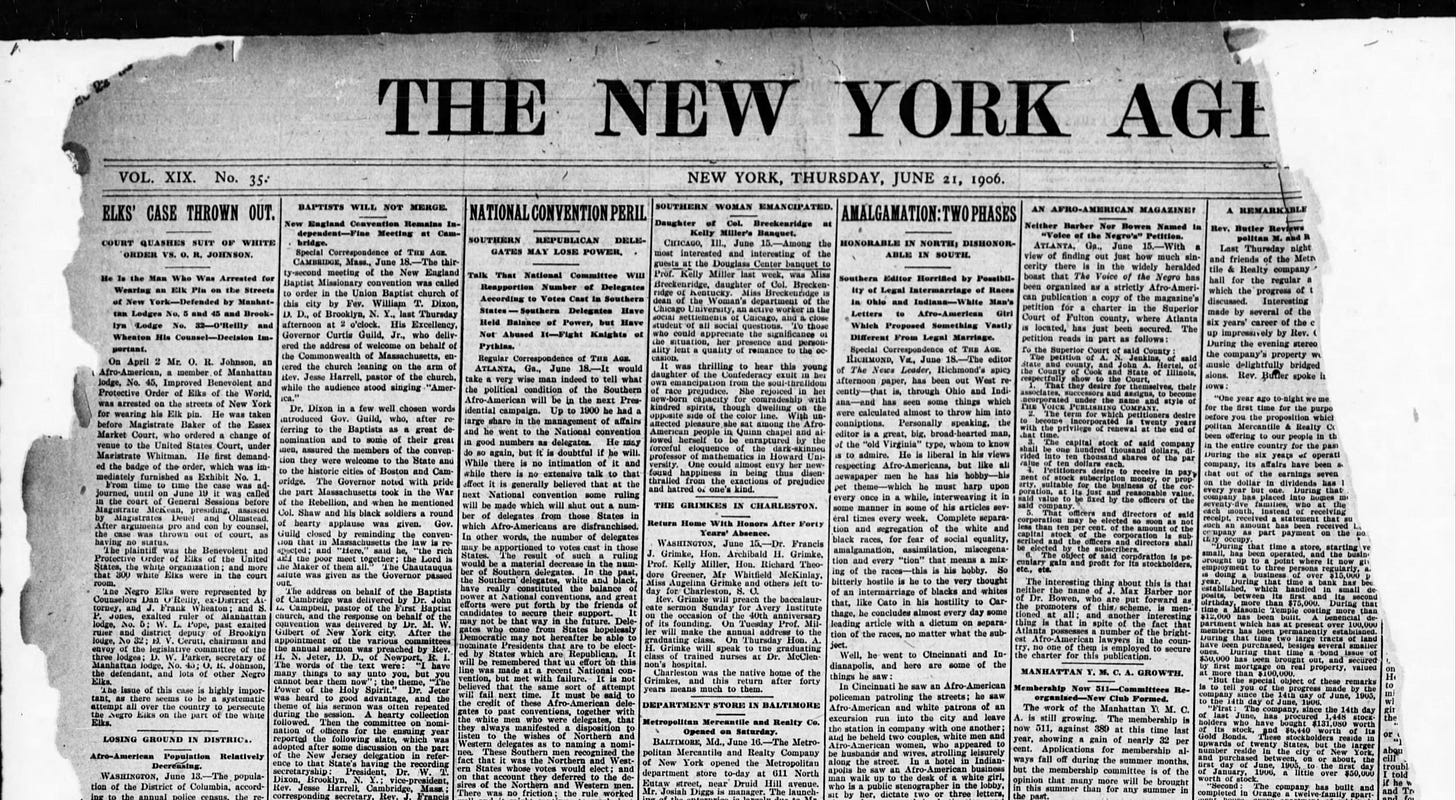

In any case, I’ll let Kerri’s work and her speak for itself and herself. I’m really excited she joined us for this inaugural edition. Kerri talks about working with Black press materials, especially the New York Age, a weekly newspaper in the eponymous city, founded by Timothy Thomas Fortune, a once-enslaved man, and how editions of the newspaper shaped her work in The Grimkes.

Could you trace the path of how you came upon these materials?

When I was in graduate school, my dissertation was on the role of the Black press as a radicalizing force. Through that, every time I’ve been researching something, the Grimke name has stood out as ubiquitous in the Black press.

Entering this project, I really wanted to look at the distance between the ways the Grimke family—both the Black and white sides—were talked about and revered, and how they talked about themselves publicly and the ways they talked about themselves and related to one another privately.

How did you first interact with them?

When I started to look at the Grimkes, I was concerned with this family beyond what the press, both the Black and white, proclaimed about them and beyond what they proclaimed about themselves. But I found that by really looking at the Black press, specifically the New York Age, which chronicled the Black community from around the country in very minute detail, both the inane and the spectacular, I found there were reports within the Black community about members of the family you wouldn’t have captured in their writing.

For instance, the Grimke brothers—Archie and Frank—are the two most well-known brothers, and yet they have a younger brother named John Grimke. And the Grimke family talked about him as being this failure. They don’t really talk about him much after he went to Lincoln University. And yet the Black press talked about him a lot in terms of his stumblings after: as a waiter, then as somebody who taught for a little while, and then as somebody who was this tragic failure. That allowed me to say that what the Grimkes were claiming about John didn’t match up to what was actually happening with him. And what did it mean that the public, the Black public, knew what was happening with John, or at least suspected, and the Grimke family denied that he existed?

What did the materials unlock for you in your work?

To talk about or challenge this tone of exceptionalism that follows the Grimkes: both the white side and the Black side. The white side has this story: they were these white women who disavowed their slaveholding lives and became abolitionists. The Black side, it’s like, they were born enslaved and they managed to become these movers and shakers within Black life at the turn of the century. And yet, ‘cause I knew and I had delved and I had worked with the Black press so much, and had seen and had jotted down over the years how much they were mentioned there, I realized that it was a burden the public put upon them. And it was something that was manufactured, whether consciously or not by all sides of the Grimke family.

Where did they lead next?

I think my knowledge of the Black press allowed me to go into the archive. To go into the Grimke papers at the University of Michigan and the papers at the Moorland-Springarn Center at Howard and look for things that I don’t know I would have looked for if I didn’t have knowledge of them through the press.

What materials weren’t you able to include in the book?

The Grimke boys’ mother—the enslaved woman Nancy Weston—her family history is fascinating because she was part of this free Black family in Charleston named the Weston family. And her sister, Lydia Weston, ended up moving to Ohio and having a group of sons who became leaders in Reconstruction politics in Charleston. So that was her family. And finding the letters between Archibald and John, their cousin, who was a Black lawmaker, and that they were very close to one another was something I couldn’t delve into in the book because it would’ve, you know, made it even longer than it became. But that correspondence between them provided a lot of insight into that African-American political leadership class that was born enslaved and were children of enslaved Black women and white male slaveholders and then became leaders in the community.

Is there a librarian, archivist, colleague, or research assistant who helped you put together the pieces from these materials?

She didn’t help me personally, but her work really articulated what I was trying to do: Stephanie Jones-Rogers, who wrote a book called They Were Her Property about white women as slaveholders and agents of slaveholding in the South. That book when it came out crystallized for me and articulated what I was trying to do in my own.

And then the Clements Library at the University of Michigan as well as the Moorland-Springarn. During the pandemic, they would send me stuff and scan stuff because I couldn’t be there physically. And it was a bunch of graduate students, you know, a bunch of them, not one, but they would, when I would text or email them and say, ‘I need this document,’ they would get back to me and scan it. Both of those institutions were indispensable. I could not have done the book without their support.

We’ll be back in two weeks with the next edition of Sources Cited. In the meantime, you can subscribe to receive it in your inbox as soon as it’s released. Sources Cited will remain free for all readers, but if you like what we’re doing, we appreciate you subscribing.