Recently, and not for the first time, I turned to botany to bring specificity to a scene I otherwise had scant details of. Maybe it’s the fixed nature of flora, an unmoving but lively background a writer can focus their gaze on, not having to worry about a creature or another walking out of one’s mental frame. Really though, for me at least, I think it has to do with names. A quick foray into plant life along the south Rio Grande had me encountering Huisache, Bernardia, Oreja de Ratón, Chomonque, Coastal Seepweed, Tepozán. Each name says something about the persons who encountered and found something in the plants—even if, often if—that wasn’t the first time.

There, clutching the ground with a stubborn refusal to die in drought or succumb to flood, were plants such as Opuntia, the prickly pear with its brilliant scarlet fruits; Yucca, the Spanish bayonet, no more than a cluster of deadly-looking spikes until it sent up a maypole of pale flowers with as many frills as a flamenco dancer’s dress; and Echinocereus, squat green cylinders covered in spines with common names like “prostate hedgehog” and “devil’s fingers.”

The above is an early section from Melissa L. Sevigny’s Brave the Wild River: The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon and speaks to a certain communion between plants and humans in this work, of naming and a movement in flora I only know from a distance. What I already knew was that the writing of Melissa’s book involved examining the letters and journals of the two scientists at the heart of this story, Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter, an opportunity that granted her a definite proximity to the people she wrote about. Reading the book, the value of those journals is apparent, but what I also came to see was how Melissa’s upbringing in the West, and her writing in nonfiction, poetry, and as a science communicator, shows on each page, in her linguistic precision and the rigor of her understanding. Right now, Melissa is the science reporter at KNAU (Arizona Public Radio) and lives in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Could you trace the path of how you came upon this material?

In 2018, I was searching for stories to tell about Grand Canyon National Park’s upcoming centennial anniversary in the digital archives of Northern Arizona University when a hyperlink popped up: “women botanists.” Curious, I clicked on it. There was only one name: Lois Jotter. She had run the Grand Canyon in 1938 with her mentor and colleague, Elzada Clover, and made the first-ever formal plant collection there. I was astonished that I had never heard either of their names. Not much had been written about their adventures—and the few stories I could find focused on their role as the first non-Native women to run the Grand Canyon, instead of describing the scientific research they did. I realized if I wanted to know more of their story, I’d have to dive into Lois Jotter’s archived papers and write something myself.

How did you first interact with it?

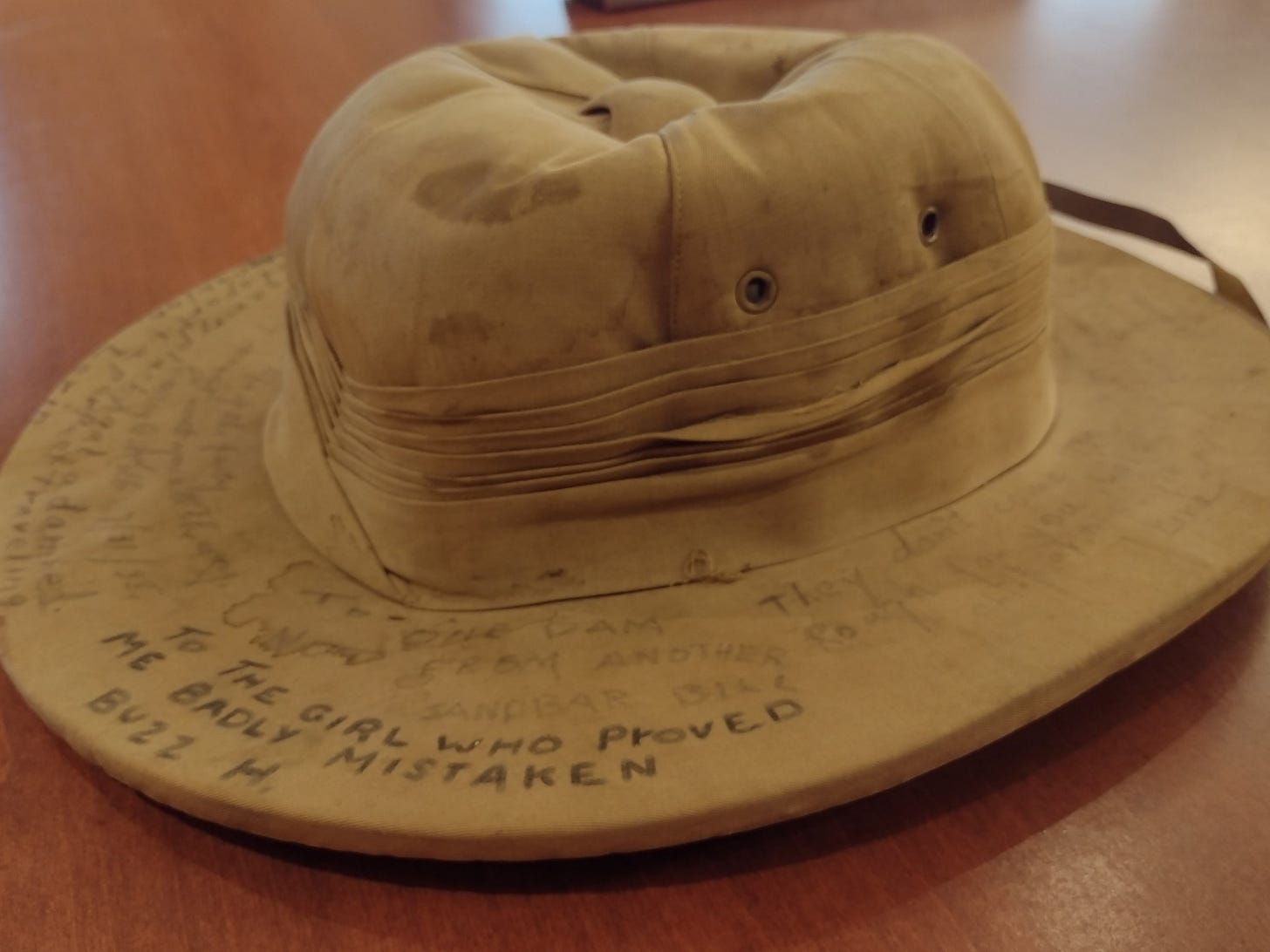

Around Christmastime in 2018 I visited the Special Collections at Northern Arizona University to see an exhibit of Grand Canyon photographs. There, on the wall, was a black-and-white photo of Jotter and Clover. The exhibit’s curator, Peter Runge, happened to walk by and I mentioned that I’d been thinking about writing something about the two women and their adventures. Peter told me to wait and disappeared into the archives. He returned with a cardboard box filled with pink bubble wrap. Inside the box was Lois Jotter’s hat—a stiff, yellow pith helmet that she wore during the 1938 river trip. Still legible round the brim of the hat were the faded signatures of her river companions, including a tantalizing note from Buzz Holmstrom, who had famously declared that women didn’t belong on the Colorado River.

What did the material unlock for you in your work?

I started writing that very day. Something about seeing Jotter’s hat made the story real to me. I wanted to know what drove her to do something so risky and audacious, after so many people told her that it wasn’t a woman’s place to run rivers. Even the hat itself said something about her state of mind: she went into the expedition literally wearing a helmet, preparing as best she could for the possibility of a serious injury, while knowing there would be no way to evacuate or call for help once they entered the Grand Canyon. From her letters I learned Jotter wasn’t the daredevil type. Like her mentor, Clover, she was driven by the desire to make a botanical collection and do meaningful ecological research. So I decided to tell the story in a way that centered Jotter and Clover’s experiences as women in science.

Where did it lead to next?

I spent most of 2019 combing through Lois Jotter’s collection, including her 1938 diary and letters, as well as materials from Elzada Clover’s archive at the University of Michigan. I published the story as a longform article in the Atavist Magazine and then connected with an agent to work on a book proposal. I signed the contract with W.W. Norton just as the pandemic shut the country down and cut off my access to other archives that I wanted to visit. Luckily, I had both women’s diaries in hand, and their voices and experiences became the heart of the story. Later I was able to fill out my research with letters and diaries from other expedition members, and I also rafted the Grand Canyon with a botany crew. That’s something I never imagined doing, and it was a thrill to get to know the river on a rafting trip, after getting to know it secondhand through archival documents. The book, Brave the Wild River, will be published this month, four and a half years after I first saw Lois Jotter’s river-running hat. A quote from the brim of that hat, in fact, is the last line of the last chapter of the book.

What materials weren’t you able to include in the book?

Buzz Holmstrom wrote a series of lovely letters to Lois Jotter during his 1938 trip down the Colorado River. Though it’s a key part of the story—showing how Holmstrom changed his mind about female river-runners—it comes late in the book and I didn’t have space to quote him extensively. The letters are incredibly funny and filled with these Emily Dickinson-like dashes. Here’s a sample, dated from Green River, Wyoming at the start of his river trip: “We were going to take a coon fox for a mascot—I was to tame him—the best I could do was to tame him to the point where I could pet him with my left hand if I let him gnaw on my right.” Or this line: “One advantage of taking such a trip in November is that there’s no danger of getting drowned as you’d be sure to freeze first.”

Is there a librarian, archivist, colleague, or research assistant who helped you put together the pieces from these materials?

Sam Meier curated the Lois Jotter Collection at Northern Arizona University as I was working through it, and Cymelle Edwards, my research assistant and a talented poet, helped me sift through all the material in the midst of the pandemic. Without them this work would have been much more difficult!

We’ll be back in two weeks with the next edition of Sources Cited. In the meantime, you can subscribe to receive it in your inbox as soon as it’s released. Sources Cited will remain free for all readers, but if you like what we’re doing, we appreciate you subscribing.