A few weeks ago, I watched Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up. The film follows Lizzy, a sculptor played by Michelle Williams, as she gets by. The manner in which she does so will be familiar to any artists reading this newsletter: sculpting in fits and starts, working for meager compensation in a job uncomfortably adjacent to those efforts she most enjoys. Much of the film shows Lizzy performing administrative functions at a small arts nonprofit (or perhaps it’s a school). She designs posters for others’ shows and—it goes unwritten, but one might assume—takes part in that defining act of nonprofits: serving as middleman between patrons and those who are patronized.

Though readers are one patron of the U.S. Poet Laureate (technically, the verbose “Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress”), one cannot say the Poet Laureate, insofar as the term defines the person, is an artist like any other. Part of their task is the generation of verse, but only if the poet would like it to be. Another has them acting as a consulting librarian to the Library of Congress. Gwendolyn Brooks, in her time, developed a reading series in Washington, D.C. where she—as the person who, however informally, cut the check—served as a patron of the art. “What does the Consultant in Poetry do?” Brooks pointedly asked in her report to the Library of Congress. One might say, in its iterations, the office’s common feature has been that of middleman between state and reader. How a laureate navigates this tripartite relationship’s other sides, in what balance, with what allegiances and requisite measure of discomfort—particularly in an artistic form attractive to countercultural forces—changes depending on who sits in that Jefferson Building office overlooking the Capitol.

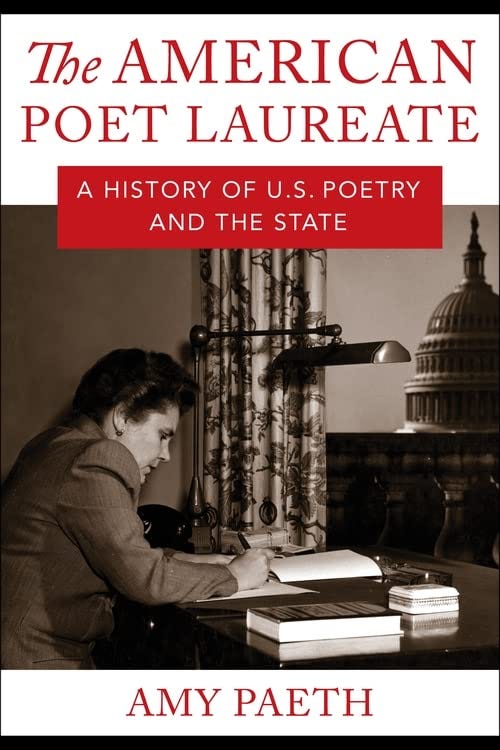

Dr. Amy Paeth set out to answer these questions and others in The American Poet Laureate: A History of U.S. Poetry and the State (out now with Columbia University Press). Dr. Paeth is a lecturer in critical writing at Marks Family Center for Excellence in Writing at the University of Pennsylvania where her research focuses on American poetry and state power, popular media, and representations of women, feminism, and postfeminism. Already, The American Poet Laureate received the Northeast Modern Language Association’s Annual Book Prize.

Could you trace the path of how you came upon this material?

I study modern and contemporary poetry; I didn’t begin as an archival researcher or “material texts person” as we called them in graduate school! However, I found that the way I could make sense of what was talked about as “the poetry wars” in my field—fights between respectable, mainstream poets versus countercultural poets—was to explore these tensions between poets, styles, values, and publications from an institutional perspective. This led me to focus not on individual poets but on institutions like Poetry Magazine, government bodies ranging from the CIA to the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), and philanthropic organizations—and I found a rich record of institutional interactions in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

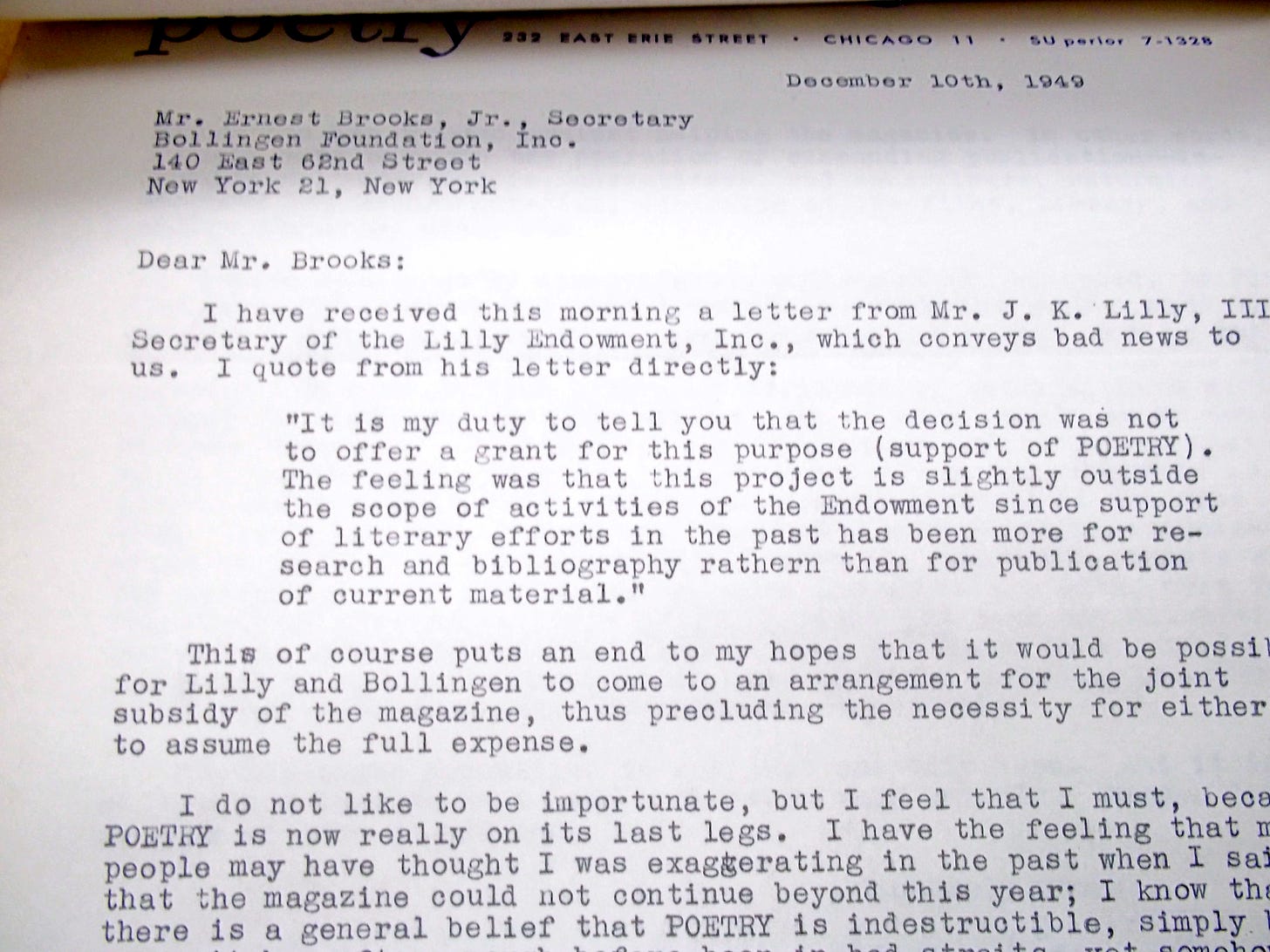

I still remember sweating on the BoltBus from Philly to D.C. for my first archival trip, back in 2011, where I stayed with a friend to spend a few days at the Manuscript Division. That is the trip where I found this document.

How did you first interact with it?

The document that excited me so much was a letter written in 1949 by the editor of Poetry, Hayden Carruth, to Ernest Brooks, secretary of the Bollingen Foundation, the magazine’s chief funder. In the letter, Carruth is despairing, warning that Poetry “was really now on its last legs.” He had been trying to secure another backer—the Eli Lilly Endowment—and as he reports in the letter, his request to the Endowment had been denied. Two things surprised me about the letter.

First, although the letter was addressed from Poetry’s editor to the Bollingen Foundation, soliciting them for funding, it was about how a different organization, the Lilly family, had denied Poetry’s funding request. This showed me how arts organizations and artists interact—not usually in pairs, but in shifting constellations.

But the second, and far more interesting thing about the letter is who this other funder was: the Lilly family of Lilly Pharmaceutical. Today, we know Lilly Pharmaceutical for Prozac and diabetes drugs.

And in 2004, the Lilly family made a donation that shocked not only the poetry world but the nonprofit world. Ruth Lilly, who became known in the news at the time as the “Prozac heiress,” made the single largest donation that had ever been granted to a nonprofit in the United States to none other than Poetry: the donation has been most commonly valued at $100 million dollars. This money resulted in a complete overhaul of the magazine’s structure and in the birth of The Poetry Foundation, which is the most central institutional player, other than universities, in the field of American poetry today. The award was controversial. As I talk about in my book, a lot of people equated this large gift with the consumerization of poetry and thought a “big pharma” gift to poetry was evil.

So, what shocked me as I looked at this document was that this had never been mentioned in popular news sources: the Lilly family had made an appearance in the poetry world much earlier than 2004! Poor Hayden Carruth had come knocking at the Lilly family door in 1949. Sitting at my desk in the Manuscript Division, I shook my head as I read the letter—wondering what Carruth would have thought if he knew that five decades later, his requests for funding from the Lilly family would finally come through—in spades. It is an incredible irony because at the time the Lilly family denied his request, and a month after he wrote the letter, he was fired as the editor of Poetry.

What did the material unlock for you in your work?

By learning what the Prozac family fortune has to do with Poetry, I realized that I was onto something. By looking at institutional paper trails—in this case, hard-to-access documents in physical library locations—I was able to access stories about the so-called poetry wars that were much richer (and more accurate) than the stories that were repeated by popular scholars in my field.

Where did it lead to next?

The exchanges between Carruth, the Lilly family, and the Bollingen Foundation became a touchstone in my research exploring the relationships between institutional players in the poetry world. It led to further archival research that is represented in my first book, where I describe how state bodies coordinated and depended on private and semi-private players to fund mainstream American poetry after World War II. My research since has shown how the state now does this funding work most expertly through private networks.

Is there a librarian, archivist, colleague, or research assistant who helped you put together the pieces from these materials?

I am so glad that you asked. My book, by looking at institutional histories, takes care to represent work of cultural production that is not only performed by artists but by administrators, secretaries, librarians, etc. Usually obscured, they are the ones constructing and preserving what we come to know as the art. For example, in my book, I talk about how Poetry office secretary Phyllis Armstrong created most of the formal output of the office during her tenure—managing the sound recordings, writing the letters, and so on. It wasn’t just Robert Frost giving a great reading.

Similarly, librarians in various capacities helped me: some of the individuals I worked with were Cheryl Fox, Barbara Bair, Michelle Krowl, and Bruce Kirby. The folks at the LoC answered my calls, rolled things on carts to my desk, helped me scan photos, and more generally helped turn my surprise and frustration at the messiness of the stories that the materials were telling into an opportunity to make available richer, more accurate stories of the “poetry wars” to scholars in my field and the general public.

(If you’d like to purchase The American Poet Laureate, Dr. Paeth has kindly offered the code ‘CUP20’ for 20% off on Columbia University Press’s website)

We’ll be back in two weeks with the next edition of Sources Cited. In the meantime, you can subscribe to receive it in your inbox as soon as it’s released. Sources Cited will remain free for all readers, but if you like what we’re doing, we appreciate you subscribing.