Sources Cited: Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette

Science reporters and the government's quiet search for a malaria treatment

The other week, I was asked to join a seminar on research and writing. As the existence of this newsletter implies, the conjunction of those two subjects is one I’ve spent a bit of time thinking about, evaluating my own processes and that of others. In the seminar, the host and I had a disagreement: does research speed up the writing process and create more efficient writers—in other words, does research make business sense for writers—or is it a time-consuming and costly process, an at-times painful process, that can only be carried out with a sense of love and necessity for the thing? What view of research turns out better writers, better researchers, better written works?

I recognize those two statements may not be mutually exclusive, but I have my doubts about the truth of the former. Typically, I’m convincing writers to conduct more research, to do so freely and with the sense that their efforts will lead to more fully-realized works. I felt like a devil’s advocate at the seminar. But for all the reasons and ways I enjoy the act of research in my own writing process, as a creative writing instructor, I’ve been careful not to fetishize it. When writers read Robert Caro and see his dictum to “turn every page,” there also exists a practical calculation. Are you able to conduct this work? Do you have the financial means to take that research trip? Do you have a schedule that allows for those trips, or do you feel safe and comfortable in those places you’d like to conduct research? If you don’t, what does that mean for a work? For an authoritative presidential biography, one’s lack of ability might very well signal the end of a project, but for other written works—those more personal in scope or when their authority derives from something else besides research—the exact amount of work necessary to start writing is a trickier thing to determine.

If research is a form of work that largely lives off the page, then reporting is a form of that research that lives nearer to its surface. It too faces these dueling incentives. On one side, there’s the drive of someone affixed to their profession not only through financial compensation but also a sense of mission. On the other side, there are conditions of the market or politics or popular society that restrict that work from taking place. Sometimes, cruelly, these broader forces lift an abstract conception of the work while simultaneously curtailing one’s aspirations to carry it out.

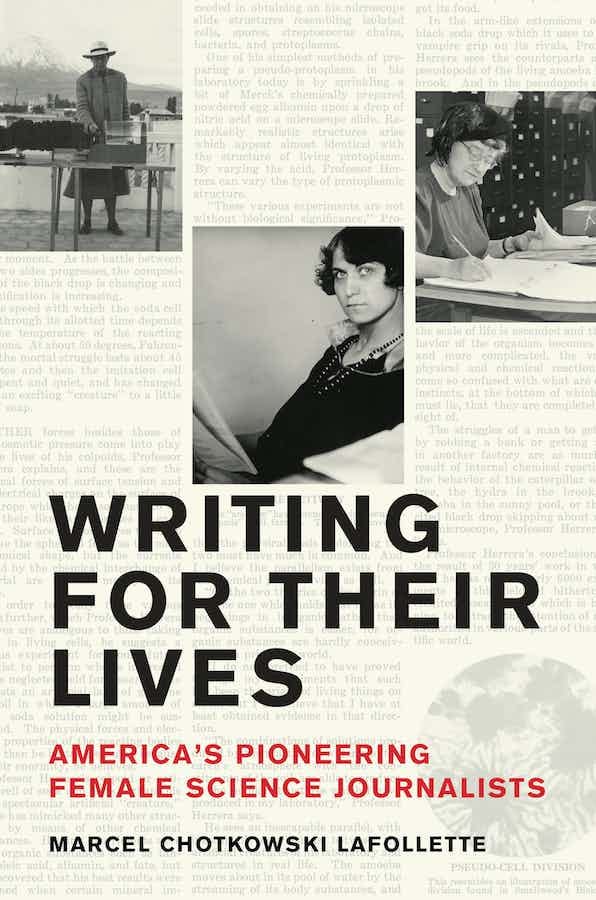

Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette, author of Writing for Their Lives: America’s Pioneering Female Science Journalists (out August 22nd from the MIT Press), details a form of this dilemma. Writing for Their Lives describes the efforts of female journalists in the 1920s through the 1950s, journalists who sought to communicate important scientific and medical information to the public as the government at times tried to prevent them from carrying out that task. Extant difficulties these journalists faced as women in a male-dominated profession increased the weight behind these forces. Most interesting were the crannies these journalists found in official regulations that allowed them to accommodate or reject guidance so that they could carry out their chosen work anyway.

LaFollette is an independent historian and writer. After spending the first decades of her career as a professor and journal editor, she turned to research and writing. She has an honorary appointment as a Smithsonian Institution Research Associate, conducting work at the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Could you trace the path of how you came upon this material?

After publishing three books based on the Smithsonian’s voluminous Science Service collections (the papers of the not-for-profit news service), and in need of a distraction while undergoing radiation therapy for breast cancer, I decided to write about the women who were among the first full-time science reporters in the U.S.1 None of these women apparently left personal papers or diaries (or, as one archivist reminds me, they are “not lost, just not yet found”). So, I focused on locating traces of their work lives: on why and how they gathered information, what standards they applied, what challenges they encountered and overcame.

Raw notes, whether scribbled by scientists or journalists, convey the energy of the moment and preserve invaluable glimpses of how scientists and journalists evaluate information. The document I want to focus on today is a typed memo by Hallie Jackson to Watson Davis and Jane Stafford from June 29, 1943. Jenkins, Davis, and Stafford were all staff members of Science Service. Jenkins was responsible for communications with the U.S. Office of Censorship during World War II, Stafford was the Service’s medical topics reporter, and Watson Davis was their boss. To me, this memo perfectly illustrates how these particular journalists responded to wartime censorship in real time.

How did you first interact with it?

The Science Service collections run from the 1920s through the early 1960s, a period of enormous change in science, the media, and world history. The papers can be frustrating in their lack of arrangement (these were the working files of a news organization) and rewarding in their flakes of gold. When I saw this document, I knew it was one of the latter.

I love marginal notes, postscripts, annotations. Historical discussions of wartime censorship generally center on the administrative and bureaucratic aspects. But here was a document that recorded the medical reporter Jane Stafford grappling with conflicting responsibilities to her readers and the law, all while she’s at her desk and on the phone with a source. How does she keep her readers informed when government regulations were so imprecise?

This is also a document that illustrates well the cooperative nature of a small news organization. Stafford might be gathering information in the field (or at a scientific meeting or on the phone to sources) but there were many more of her colleagues back in the office handling the other aspects of publishing, from circulation and advertising to interacting with the printer to, as in this case, interfacing with government censors. Everyone worked toward the same goal: to deliver accurate, current, informative news about the science of the day.

What did the material unlock for you in your work?

Readers unfamiliar with the history of science might naturally assume that the important World War II secrets involve the atomic bomb. Considerable government attention was also given, however, to medical information. Quinine, which was then the standard treatment for malaria, was in short supply. Given the military action in the Pacific, the hunt was on for other effective drugs or other botanical sources of quinine. Hallie Jenkins’s memo to Davis and Stafford reports that her contact at the U.S. Office of Censorship has “called to say that the Army has developed a new cure for malaria which contains no quinine. Should help terrifically in jungle war-fare. The only ‘catch’ is that nothing can be published about it!”

And yet, as Stafford wrote in a follow-up memo stapled to this page, the government regulations were “not very distinct on this subject.” She knew that if true, the new treatment would be important medical news of interest to her readers, so she called one of her sources to confirm the information and the extent of the restrictions (and, presumably, to discern when she might eventually be able to write about the breakthrough).

Where did it lead to next?

Episodes like this illuminate the significance of definition and clarification in science reporting, and how conscientious journalists verify information. What does it mean to be told not to publish “any information whatever regarding” a scientific topic? As you look at this document, imagine Jane Stafford with the telephone receiver to her ear: calling her sources, asking questions, scribbling notes.

This particular document also emphasizes the importance of archival preservation related to “time and space.” Letters by famous people are fascinating of course, but sometimes these seemingly ephemeral notes can also assist in the telling of history. This document was created in 1943, in the heat of the moment and when newsrooms were not digital. The preservation issues are obvious. The memo was glued to a sheet of paper which was later stapled to other related memos and carbons before being filed in the organization’s morgue. For a historian, flipping through the stapled pages is an exercise in intellectual and historical excavation. On this particular document there are also layers of annotation, written in pencil, in different handwriting and intensity, as well as tiny smudged date stamps.

There is a photograph of Jane Stafford in the Smithsonian collections, telephone held up to her ear and with her “name and date” stamp device visible on the desk. Every time I see her penciled scrawl on a piece of paper, I think of her, writing for the lives of her readers.

We’ll be back in two weeks with the next edition of Sources Cited. In the meantime, you can subscribe to receive it in your inbox as soon as it’s released. Sources Cited will remain free for all readers, but if you like what we’re doing, we appreciate you subscribing.

Science on the Air: Popularizers and Personalities on Radio and Early Television (University of Chicago Press, 2008); Reframing Scopes: Journalists, Scientists, and Lost Photographs from the Trial of the Century (University Press of Kansas, 2008); Science on American Television: A History (University of Chicago Press, 2012).